This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

A wave of new companies are crafting financial incentives to block emissions from oil and gas wells that are near the end of their life spans—and orphaned wells with no clear owners. Yet doubts persist about project oversight and the ethos of the market.

Tyler Crabtree was working in the oil and gas industry in North Dakota, trying to prevent methane leakage from well sites, when he started “soul searching” for a better way to address climate change. He knew it was becoming ever more severe and felt the industry should do more to address it.

“It really opened my eyes to how a lot of operators out there are not spending the appropriate amount of dollars on clean operations,” he said.

Crabtree went on to found CarbonPath, a Houston-based company offering a new class of carbon credits, or offsets, that come from plugging oil and gas wells. He realized that most of the wells in the United States produce relatively little oil and saw an opportunity to incentivize shutting them down early, locking fuel under the Earth’s surface to halt methane emissions that heat the atmosphere at 80 times the rate of carbon dioxide.

CarbonPath is part of an emerging industry that pairs carbon market financing with oilfield service providers to plug wells and generate carbon credits, which it then sells to corporations trying to meet emissions reduction goals and individuals seeking to offset their own negative climate impacts. The new companies are promising to bring verified, high-quality credits into a carbon marketplace that has been fraught with calculation errors and unresolved ethical questions.

“What we’re seeing particularly in the voluntary carbon market is a lot of questions about ‘how can we trust that these carbon credits are real,’” said Martijn Dekker, chief executive of ZeroSix, another Houston-based company offering carbon credits for the “early retirement of oil and gas wells.”

CarbonPath has two different methodologies for generating a carbon credit. The first is for verified plugging of what Crabtree, the company’s CEO, refers to as marginal wells, which produce a small but economically significant amount of oil or gas and typically leak methane. The credit value is determined by an estimation of the potential carbon emissions of fuel left in the ground. Other companies, including ZeroSix and Austin-based ClimateWells, have developed similar methodologies.

“It’s a market-driven solution,” Crabtree said. “If you put a price on carbon that’s acceptable and use the voluntary carbon market, you can incentivize the shutdown of these wells earlier in their lives.”

CarbonPath’s other methodology is for orphaned wells that are inactive, have no legally responsible owner, pose a threat to groundwater, and in many cases are also leaking methane and toxic chemicals. As with the marginal wells, methane emissions from the sites are measured or estimated, and the offset is based on how much methane is prevented from leaking into the atmosphere.

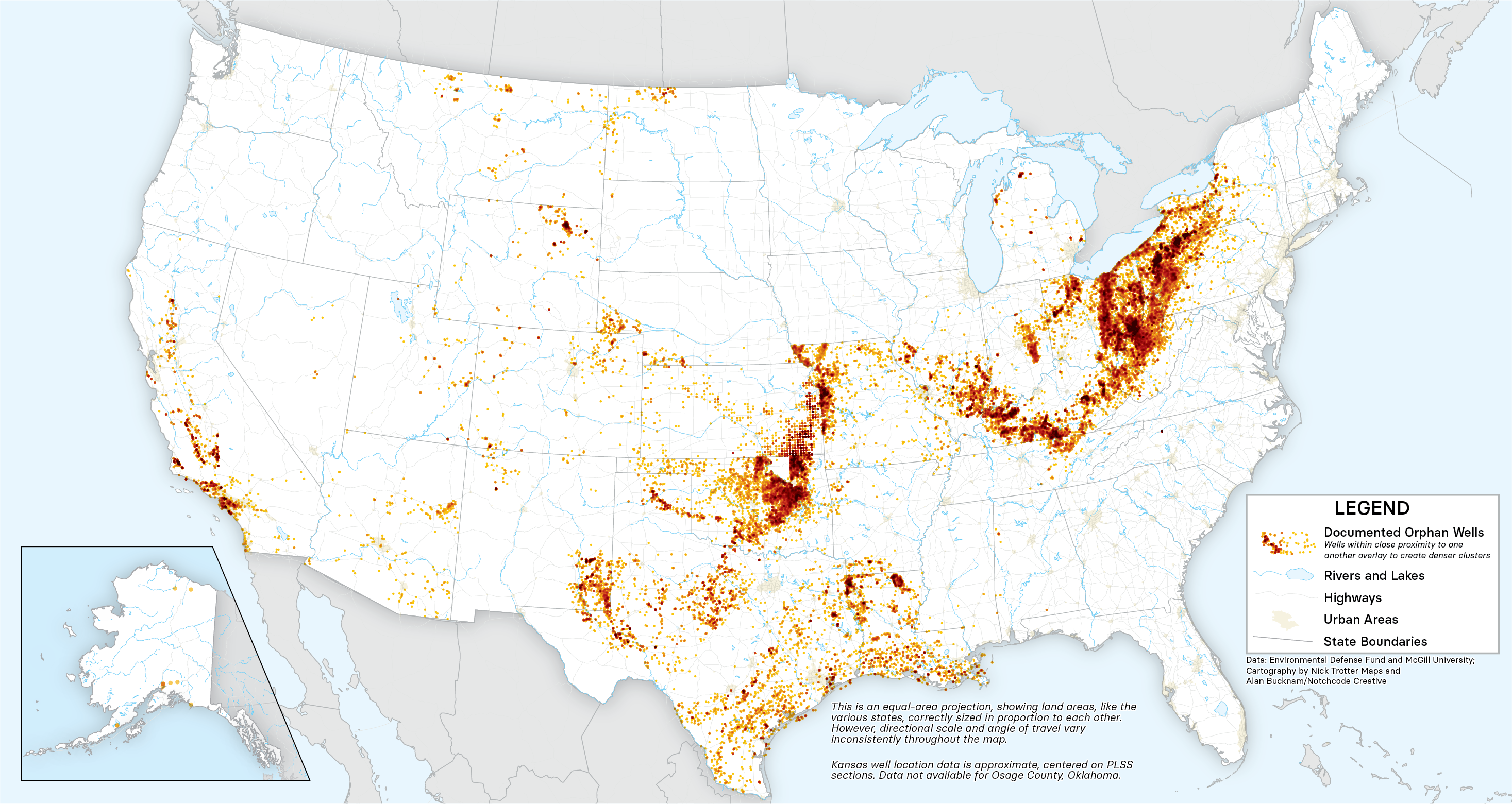

More than 120,000 orphan wells are documented in the United States, according to a study from the Environmental Defense Fund, or EDF, but as many as 800,000 more are thought to exist.

With Limited Funds, Just ‘Scratching the Surface’

At an average price tag of $75,000, plugging oil wells is not cheap. Typically, as wells get older and produce less, they are sold to ever-smaller operators, and when the operators cannot afford to plug the wells, they often abandon them.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in 2021 steered $4.7 billion to state agencies to help plug orphan wells. But Adam Peltz, the director of the EDF’s energy transition program, said there was nonetheless “a huge shortage” of money to get the job done. “We’re only scratching the surface,” he said.

CarbonPath launched its orphan well methodology in May, beginning work on 42 wells in Colorado. Crabtree said he wants to see more oil companies contribute funds to plugging such wells.

Meanwhile, ClimateWells offers emission-reduction credits for plugging oil and gas wells “earlier than they would have been plugged otherwise,” according to its CEO, Reid Calhoon. The company’s methodology factors in both methane and benzene emissions.

He and his team spent two and a half years studying emissions from orphan wells but ultimately decided to offer carbon credits only for shutting down wells that are still producing. Calhoon said he feared that using carbon credit financing to plug the other category could create an “adverse incentive for companies to continue to orphan their wells.” Instead, ClimateWells encourages oil and gas producers to plug wells that are late in their life cycle, thereby preventing them from ever becoming orphaned.

“If our program expands, we believe it stops the orphaning of wells all together,” Calhoon said. ClimateWells’ first project is underway in downtown Los Angeles.

The EDF estimates that more than 565,000 marginal wells are operating in the United States. They represent about 80 percent of all actively producing wells but produce just 6 percent of the nation’s oil and gas supplies, the data show.

Before starting ZeroSix in 2021, Dekker was a vice president at Shell Oil, where he worked for 25 years. ZeroSix is now planning to plug its first wells in July or August and is in talks with a number of oil and gas companies that are considering shutting down their wells early in return for carbon credits, Dekker said.

Demand for quality carbon offsets is high. But Peltz of the EDF, who describes himself as an “intrigued skeptic” on the viability of a carbon market based on plugging wells, said one of his biggest concerns was “additionality.” On the voluntary carbon market, additionality is the principle that financing made available through carbon credits must be used for climate-friendly projects that otherwise would not be possible.

In the case of marginal wells, Peltz is worried about the potential “moral hazard” of subsidizing oil and gas operators to shut them down when those companies are legally obligated to plug them eventually anyway. “There’s kind of a gold rush going on with essentially no oversight,” he said.

With orphan wells, Peltz sees a more clear-cut case for why the carbon financing is “additional”—in theory, it is the only way that those wells will be plugged— but notes a potential crossover with federal funds targeting the most polluting orphaned sites.

Like CarbonPath, the nonprofit American Carbon Registry has developed a methodology for creating offsets from avoided methane emissions by plugging orphan wells. Maris Densmore, the director of engineered solutions at the organization, said it chose to focus only on orphan wells after “questions around additionality” were raised through its peer review process and in public comments.

“We measure how much [methane], we plug it, make sure it’s not leaking anymore, and that’s where the credits are generated,” said Densmore, an environmental geologist. “There’s not a lot of wiggle room on the numbers.”

The methodology is already being used to plug orphan wells in Oklahoma. ClimateWells is looking into using the registry’s method to offer credits.

Beyond the climate benefits of reducing methane emissions, Densmore said the development of a carbon credit market will provide “an opportunity for well pluggers to have a stable and reliable work stream that they can hang their hats on.”

‘A License to Continue Emitting’?

When it comes to the carbon market as a whole, however, there are many doubters. Barbara Haya, director of the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project at the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that it’s time to start moving away from carbon trading altogether. Beyond what she views as rampant overcalculation of the environmental benefits, she sees offsets as “a license to continue emitting, and it’s hugely damaging.”

While Haya is not familiar with the specifics of the various well plugging methodologies and agrees that many projects associated with carbon markets have accomplished good things, she contends that they fail to acknowledge the urgency of the climate challenge.

“We are in a climate emergency and we don’t have time for false reductions,” said Haya, who has studied carbon credits for 20 years.

Haya finds the calculations for many carbon credits “immeasurable and inherently uncertain” because they “measure emissions reductions against a counterfactual scenario”—namely, projected releases of methane or carbon dioxide—”that never happened.” And Peltz cites an array of unanswered questions about the financing, including “accounting, additionality, perverse incentives and moral hazards.’’

“I don’t think that those factors have been adequately considered and vetted in this rush to bring carbon finance into the well-plugging universe,” he said.

The companies looking to sell carbon credits based on well plugging counter that they have criteria built into their methodologies that makes the offsets verifiably “additional.” Because the marginal wells targeted are currently providing economic benefit to the oil and gas operators, they say, they would not be plugged early without some incentive.

“I have little time for people who want to have the perfect solution, because it may take 20, 30, 40 years to get that perfect solution,’’ Dekker said. “And by that time, the planet’s probably cooked.”

Calhoon of ClimateWells acknowledges the worry that oil operators will simply drill new wells in other places, canceling out any emissions reduction benefit from plugging older ones. In the carbon credit market, this notion is called “leakage,” meaning that the emissions are not prevented but essentially moved.

But he said that ClimateWells relies on research by “leading oil and gas emissions think tanks and institutes to develop custom market leakage accounting.” And he maintains that the “leakage” analysis applied to the operator whose wells are plugged is “precise, very conservative and scientifically peer-reviewed.”

From their progressive names to their accounting methods, the new carbon credit companies are particular about the way their evolving business is framed. Crabtree, for example, said he “hates” the word “offset” because it fails to capture the company’s mission. He prefers to think of CarbonPath as creating “positive climate projects.”

“We’re not carbon avoidance,” he said. “We’re not carbon removal. We’re carbon eliminating. We’re locking it back in the ground.”