In neon vests and hardhats, the biologists and archaeologists who march resolutely towards hulking piledrivers almost resemble the workers operating them. But blood red letters spell ECOCIDE on the long canvas banner that these protesters carry like a cross through stripped-bare stretches of what used to be jungle.

In Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, two-thirds of all freshwater in the country sits just 10 to 20 meters below the surface. But since 2020, the military has filled wetlands, driven concrete piles through the aquifer and clear-cut swathes of Latin America’s second-largest rainforest to make way for President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s flagship railway project: the Tren Maya.

Since the train’s inception in 2018, officials have kept the public in the dark about its environmental impacts. The train cuts through 2.87 million hectares of jungle and over half of its route traverses 177 communally-owned and managed Indigenous territories, but the government still has not divulged the potential ecological effects of the project, especially when it comes to one key resource: water.

“The great question is: what’s going to happen with at least nine thousand piles inside of the aquifer, in karstic [water soluble] soil?” asked Guillermo D. Christy, a water quality specialist and member of Cenotes Urbanos, a conservation and cave science group. Christy and dozens of concerned citizens gathered outside of the train’s fifth tram in Playa del Carmen on June 3 to protest the ongoing lack of transparency about the train’s environmental impacts. “We have the right to know what is going to happen,” Christy said.

The 1,525 kilometer railway consists of seven trams that will whisk tourists and industrial products across five states—Yucatán, Quintana Roo, Campeche, Chiapas and Tabasco—and connect the peninsula to global export markets. Sixteen stations and 12 stops will create new urban centers in rural areas that López Obrador hopes will bring “social and territorial order” to the region by catalyzing real estate, industrial agriculture and tourism development in Mexico’s long-neglected, ethnically Indigenous Southeast. The region has some of the highest rates of poverty in the country.

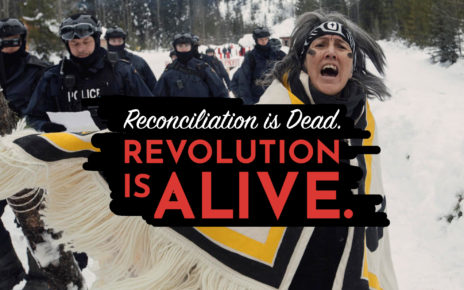

Organizations such as the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA) and the United Nations (UN) have lambasted the government for launching construction without adequate environmental impact assessments and thereby violating the rights of Indigenous communities to prior consultation and a healthy environment.

“Where is the water in Mexico? It’s in the Yucatán Peninsula, where Mayan communities are,” said Aldair T’uut’, a Bacalar community member and member of the Assembly of Defenders of the Mayan Territory Múuch’ Xíinbal. “It is very grave that [the military and the government] are violating these environments and these communities—not only for us as Mayans, who they will end up killing, but also because they will kill themselves and the planet. We are in a critical situation in which the climate is changing and in which there will be a tremendous water shortage.”

In 2022, Lopez Obrador declared the project to be a matter of national security to bypass social and environmental safeguards and evade injunctions by Mexico’s own judicial system. A year later, the President announced that Mexico’s Secretary of National Defense, SEDENA would take over construction.

The military’s role in construction has garnered national and international condemnation and has been especially controversial on trams five and six of the train, where the Train’s tracks perforate delicate limestone caves atop the longest underground river in the world and UN-designated Ramsar Convention wetlands of international importance.

With Lopez Obrador preparing to inaugurate the project in December 2023, calls are growing louder for oversight and adequate environmental impact assessments to protect the country’s freshwater supply.

Biologists argue that the Yucatan Peninsula already faces myriad threats to water quality. Recent studies have documented the presence of agrochemicals in breast milk as a result of runoff from industrial farming in rural areas of Yucatán state. Meanwhile, in areas of Quintana Roo such as Playa del Carmen, drug consumption and unbridled tourism development have contaminated local waterways with traces of cocaine.

At the same time, the physical damages to caves, aquifers and fragile estuaries from Cancún to Chetumal as a result of the train’s construction have drawn international condemnation and catalyzed widespread protests by environmental groups, Mayan land defenders and concerned members of the general public.

With the populations of 18 municipalities on the train’s route expected to grow by around 40% by 2030, these groups are begging for an answer to one question: what about the water?

Tram Five: Perforating the Sac Aktun Cave System

On a searing hot June day just before the United Nations International Day of the Environment, protesters stopped construction on the Train Maya’s fifth tram in Playa del Carmen and screamed a message they’d been trying to make clear for years: “You can live without a train; you can’t live without water!”

Since 2022, citizens of Playa del Carmen have walked miles of deforested jungle along tram five of the train to plead for adequate environmental impact statements. They warn that this section of track could contaminate fresh drinking water for over 1.8 million people by collapsing delicate cave ecosystems that connect to the longest underground river in the world, the Sac Aktun cave system.

Ongoing collapses and contamination from steel piles and diesel could threaten Mexico’s largest reserve of freshwater in a region that already faces severe droughts and overconsumption by tourism. Multiple cave collapses have already been documented. Just this month, an excavator collapsed in the Leona Vicario cave on tram five of the train.

Grupo México, one of tram five’s main construction agencies, cited the “technical impossibility” of safely constructing the section of the train by the deadline and pulled out of the project in 2023.

“[Our movement] is not against a train, it is not against development, it is not against the people who are seeking work and health,” explained Octavio del Rio, an underwater archaeologist and member of Cenotes Urbanos.

“It is against where [SEDENA] is constructing it, where they aim to build.”

Tram Six: Bacalar and the Chac Estuary

Further south along the train’s route, just outside of Bacalar’s famous Seven Color Lagoon, the sound of dynamite blasts shattered birdsong and material banks in one of the lagoon’s vital arteries: the Chac Estuary.

On July 6th, SEDENA began filling a waterway in the 9,500-hectare wetland with more than 5,000 tons of asphalt and railway ballast. They planned to open up a 60-hectare passageway through the estuary, which connects the Bacalar Lagoon to the Rio Hondo and serves as a vital flood prevention mechanism by draining water away from population centers such as Chetumal and Huay Pix.

Without drainage through the estuary and the savannah alongside it, these areas would be inundated during heavy rains.

As soon as the public got word that SEDENA was preparing to pave over one of the region’s key sources of freshwater without presenting a proposal or impact assessment to the regional government, protests began to stop construction and demand answers.

According to community members and reporting by El Universal, the military explained that filling the waterway was a temporary solution, but then backpedaled and said that construction workers had begun filling the estuary as a result of “human error.”

“It’s funny, because then the tubes that they put there were also because of human error—they arrived there by mistake,” T’uut’ explained on the Assembly’s Múuch’ Xíinbal’s radio program, La No-Radio.

“It’s clear that [the military] had the intention to cover the estuary and pass over it, just as they’ve passed above cenotes and caves,” T’uut’ said.

“It’s a planned error and it’s an error that they have been committing since the beginning of this project, poorly named the ‘Tren Maya.’ Mayans never asked for this train and we don’t want it to pass—not on a bridge, nor flying, nor in our name.”

The Future of Mexico’s Water in the Era of Climate Change

With the specter of climate change haunting Mexico, Mayan community members like T’uut’ and Alexis Jooy Juuj, who is also a member of Múuch’ Xíinbal, are worried about what the future holds for their culture and for the environment if the train is constructed.

The Yucatan’s aquifer won’t be able to catch up with massive tourism increases. According to a report released by the Regional Water Program, just five major cities—Mérida, Cancún, Playa del Carmen, Ciudad del Carmen and Campeche—will consume almost as much water as the entire Peninsula by 2030.

And in Playa del Carmen and Bacalar on trams five and six, pollution in the aquifer, changed water flows, longer droughts due to deforestation and changing rain patterns combined with over-extraction to support tourism threaten to strain supplies even further.

“We won’t be able to buy [water] with the jobs created by the train,” Juuj stressed. “What they pay us won’t be able to buy what really matters: water.”