Introduction

In Part One of Growing Sovereignty, I drew upon conversations I had with four individuals Indigenous to various areas across Turtle Island. During these discussions, I felt very grateful to be given the opportunity to not only learn from them but to also be in a unique position to amplify their voices while simultaneously spreading and sharing the information I have been so lucky to receive.

Each conversation, while different, was fundamentally linked with a common theme: Indigenous Sovereignty and regenerative stewardship of the Earth. Embracing the role of a steward to Mother Earth is critical, especially in the context of future generations. What is it that we are passing on to our children, not just physically but mentally? Are we equipping our children (and therefore ourselves) with the tools necessary to put an end to Capitalism and Settler Colonialism’s destructive reign over the Earth?

Stewardship of Mother Earth must include Indigenous Sovereignty for all Nations. Meaning, in one aspect, the right to self-determination and management of land however seen fit, without unwanted outside intervention or contamination. Amanda Rouillard, from the Santee Sioux Nation, has been doing research about her Tribe’s contaminated water and how the water came to be polluted. Part two of the Growing Sovereignty series will focus on the conversation Amanda and I had, alongside the history of water colonialism and how it specifically affected and continues to affect the Great Sioux Nation.

Water is Life, and Indigenous Nations are and have long been adversely affected by contaminated water. Reversing destructive modes of water and land management requires acknowledging and understanding this history while moving towards a mode of existence which is predicated around Decolonization, Indigenous Sovereignty and the Regeneration of Mother Earth.

Mni Wiconi: Water Is Life

Amanda explained how “Santee was established by President Andrew Johnson’s executive order of 1886, as a home for the Santee Sioux Nation after a failed relocation attempt in South Dakota, which resulted in the majority of the tribe dying from starvation,” she described growing up in Santee “without access to potable water sources where blue refillable five-gallon jugs are the normalized representation of drinking water.”

The colonization of Turtle Island is a history of displacement, theft, mass murder, and destruction of Indigenous ecosystems, all of which are inherently genocidal. The conversation Amanda and I had illustrated how her Nation and Home suffered from many of the same colonial evils, which have plagued Indigenous Persons across Turtle Island for hundreds of years.

Throughout the history of sustained settler violence, Indigenous Nations have been forced, without consideration or consultation, to endure the most devastating effects of land and water “development” projects. The Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires- today often referred to as The Great Sioux Nation,) specifically was victim to massive water/ land management projects/ policies, which were designed to benefit settlers, ignoring any negative consequences the projects posed to Sovereign Indigenous Lands and the people living on them.

One such policy came about during the civil war era: the 1862 Homestead Act provided that any citizens who had not taken up arms against the U.S government could claim 160 acres of so-called “government land.” But the land being offered up to white people (Native, Black, all non-white persons were categorically excluded from attaining such land) was not the United States’ land to give away. It was, in fact, stolen Indigenous Land.

In “Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance,” written by Dr. Nick Estes, he explains how “One and a half million white families gained title to 246 million acres of Indigenous lands– an area nearly the size of California and Texas combined—under the Homestead Act, with the added value of federally subsidized irrigation.”

The Santee Nation was negatively affected by the Homestead Act; Approximately 50% of Santee’s Land was stolen and occupied by white settlers. What occurred under the homestead act set a further precedent for stealing and destroying Indigenous Persons’ land/water without any good faith consultation of the affected Nations.

The Homestead Act’s legacy and its negative consequences for Indigenous persons continues to this day because, as Dr. Estes observed, “A quarter of adults alive today in the United States are direct descendants of those who profited from the Homestead Act’s legacy of exclusive, racialized property ownership and economic mobility, a legacy that categorically excluded Black, Indigenous and other non-white peoples.”

Fast forward to 1933, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Fort Peck Dam was approved, and construction began, employing up to 10,000 people at some periods. The project was a part of the New Deal and was proposed within the 308 Report, a four-year study on the Missouri River conducted by the Army Corps of Engineers, in response to massive flooding in 1927.

While the New Deal is often looked back upon fondly as a period of economic invigoration and rebuilding, examining the building of the Dam reveals a sinister aspect to this part of history. Indigenous Persons were forced to endure mass displacement, destruction of their homes, land and subsequently their general way of life, and those were only some of the immediate consequences; there remains to this day lasting negative consequences of the Fort Peck Dam and the dams that were to come.

“… the dam’s history is well-publicized and well-remembered as an economic boom and engineering marvel…,” said Estes. He continues by bringing to light “the largely untold and undocumented history of the removal of 350 Nakota, Dakota, and Assiniboine families on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation and the flooding of earlier Indian Affairs irrigation projects that had benefited Native farmers.”

The Fort Peck Dam construction and the resulting destruction of the Fort Peck Reservation paved the way for the 1944 Pick-Sloan Flood Control Act; Estes explains how “a similar process would repeat itself: postwar employment and river development projects would come primarily at the sacrifice of Indigenous lives and lands.”

Five dams were proposed and built under these new laws; 611,642 acres of land were flooded in North and South Dakota. 309,584 acres of this was Indigenous land. Estes continues painting a bleak but all too true reality: “Entire communities were forever submerged … by design, the Pick-Sloan plan was a destroyer of Nations.”

One of the Dams proposed and built under the Pick-Sloan Plan was Gavin’s Point Dam, which resulted in flooding 593 acres of Santee’s fertile, wooded bottomlands along the Missouri River. What was flooded, was some of their most productive agricultural and pastoral land in the Nation.

The Pick-Sloan Dams were created with the intention of giving white communities irrigation access to help make their (stolen) farmland more productive, while also ensuring that white towns did not experience mass flooding. This same consideration was not given to any of the Indigenous Nations who were directly affected by the Dams. Instead, the Sovereign Nations were forced to relocate while their productive fertile lands were permanently submerged.

In addition to the long-lasting impacts of their fertile land being stolen and flooded, the Santee Nation to this day does not have access to potable water. Indigenous Nations are adversely affected by water contamination across the so-called U.S with 58 out of every 1,000 Native households lacking plumbing compared to only 3 out of every 1,000 white households.

Amanda, expanding upon water inequality, expressed how “reservations are historically underserved when it comes to access to potable water sources, typically a result of poor tribal and government structure and lack of economic resources. An estimated 1 in 6 people within Indian Country do not have access to safe drinking water, showing disproportionately impacted Water Injustice.”

Exacerbating these injustices is the continuation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations being forced (again, without legitimate consultation,) to sacrifice their land and clean water for environmentally destructive energy projects. Two recent and ongoing examples (there are many more,) being: Standing Rock’s resistance against the Dakota Access Pipeline threatening to contaminate the Missouri River, and the Wet’suwet’en Nation resisting Coastal Gaslink’s pipeline project threatening to contaminate their freshwater source.

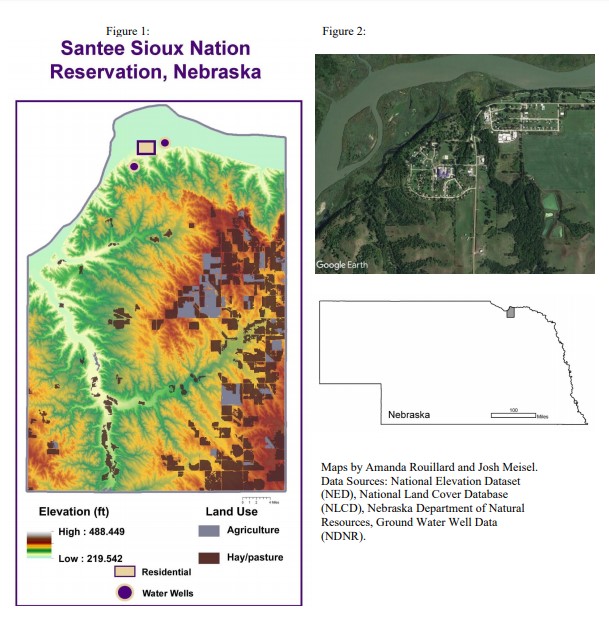

Growing up without potable water has inspired Amanda to understand why exactly this was the reality for her and her Tribe. While she was in Haskell University’s Environmental Research Studies program, she gathered data pertaining to “patterns between land use, elevations, and floodwaters on drinking water quality for the Santee Sioux Nation,” and through her research, she discovered how “livestock pastures and septic lagoons are two primary point-source pollutants of total coliform bacteria, specifically fecal coliform, in groundwater wells used for the reservation. Floodwaters, channelized runoff, and high concentrations of bacteria will further degrade water sources used for drinking water within Santee.”

Santee and its members live in the lowest area of elevation relative to the sources of water contamination. Local cattle farmers and septic lagoons are a major source of water contamination as “elevation plays an important role in how water moves through the environment and on water quality.” All sources of water contaminants are at much higher elevations than Santee’s groundwater, “making it easier for these bacteria to gain access into the water supply.” Amanda explained how “Groundwater resources have the potential to be strongly impacted by climate change,” because “[an] increase in frequency and intensity of flooding events has the potential to escalate bacterial contamination,” and “increasing temperatures boost microbial growth, and with insufficient treatment or distribution systems, water is more prone to contamination.”

Amanda’s research paper brings to light the deficiencies in the system designed by the U.S government. “The location of Santee was a decision made by the federal government, which forcibly removed my ancestors from their Indigenous homelands and placed the population in a location prone to poor water quality,” stated Amanda, putting into focus the genocidal history her Nation has been forced to endure, and how it continues to this day.

In addition to the historical displacement responsible for creating this geographic dynamic in the first place, it remains difficult to fix water contamination because “tribes are recognized as domestic-dependent nations by the United States government.” Amanda continues, explaining how “The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) handles relations between tribal nations and the United States government. History between these entities formed a distrust experienced today.” In addition to justified distrust, “complications occur when discussing rather or not potable water sources are a tribal, state or federal issue… Such complexity makes it difficult to contest the right to safe drinking water in many Indigenous communities.”

The last time a septic lagoon was replaced was in 1993, yet replacing the lagoons is only a band-aid solution that does not address the root cause of water contamination. The lagoons are simply buried, and new ones are built right next to the older ones. Issues of water runoff and channelization continue to affect the Santee Nation and will continue to negatively impact water quality until the root causes of water contamination are fundamentally addressed.

When asked what “Mni Wiconi” means to her, Amanda explained how “Water is life, sustenance, and medicine that every living organism on Mother Earth deserves. It is not only a substance composed of hydrogen and oxygen; water is sacred, a gift from the Creator.”

Viewing water as sacred represents a shift in thinking capable of disrupting and ending the worldviews and systems that continue to justify endless extraction, exploitation, and destruction of land and water. A shift in thinking is certainly possible and necessary to stop this destruction and additionally necessary to halt climate collapse and global warming.

“Indigenous peoples are and will continue to be the most impacted by climate change, however, they are rarely ever consulted on such issues,” said Amanda, outlining solutions continued and emphasizing how, “A collective voice must be created among Indigenous people with community collaboration among tribes, within and outside of Turtle Island. We must Indigenize science to ensure Indigenous-focused research on Indigenous issues.”

True Decolonization means legitimate self-determination for all Sovereign Indigenous Nations regardless of federal recognition of reservation status. This effort necessitates giving Land Back Now to the original inhabitants of Turtle Island, and ensuring Sovereign Nations have final authority over their land and what kind of projects would be allowed. Decolonization means an end to settler colonialism and capitalism.

Additionally, decolonization and Indigenous Sovereignty require a shift in thinking which emphasizes our responsibility to be stewards of Mother Earth. Wanton destruction of sacred Indigenous lands and perpetual fossil fuel extraction at the core of climate collapse has created a situation where there is nothing sacred within the jaws of capitalism and settler colonialism. The Earth and Water are viewed as commodities to be controlled, re-channeled, extracted, poisoned, and ultimately wasted and desecrated, as seen with the Santee, Wetsu’wet’en, Standing Rock, and countless other examples.

Solutions to settler colonization cannot lay on the shoulders of Indigenous Nations alone. While white allies should follow the lead of Indigenous and Black leadership on the path to decolonization, what must be done will include every being on Earth. A fundamental shift in our consciousness and mode of existence must be geared towards a system of regenerative stewardship of the Earth and all its inhabitants including humans, which means engaging in thoughtful cooperation and reconciliation with one another.

Modes of being which embrace regenerative stewardship rooted in cooperation fly in the face of capitalism’s exploitative, destructive, and alienating essence. Systems of thought which insist on the status quo being unchangeable ignore thousands of years of relatively peaceful existence before colonialism reached the shores of Turtle Island, and erase the genocidal violence which imposed this destruction and alienation.

Part one of Growing Sovereignty called for an end to Industrial Agriculture, heeding the call of the Indigenous interviewees. Stopping the dominant mode of agriculture rooted in laws of exploitation must occur to begin tearing down the lasting effects of the Pick-Sloan Plan, alongside all other evils committed in the name of settler colonial development including ecocide.

Explaining the shift in consciousness which must occur to ensure water is no longer destroyed, Amanda described how “we need to get rid of the normalization of ‘western’ uses and views of water. In our current system, water is no longer sacred, instead, it’s disrespected, misused, and polluted. Not enough people love or even care enough about water to know where their own tap comes from. It only becomes an issue when the tap stops flowing.”

She continued: “As a whole, society needs to reconnect with water and realize how essential and important it is to care for our water sources. As Indigenous people, we need to take control of our water jurisdictions, to make sure our water, land, and laws are protected and that we are included in these conversations.”