On June 5, 2022, Indigenous rights advocate Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips ventured to the heart of the Amazon Rainforest and never were seen again. The search for Phillips and Pereira gained considerable attention in Brazil and around the world, where Phillips’ reporting in The Guardian about Brazil and the Amazon was widely known. From the search’s start, however, the odds of finding them alive were slim.

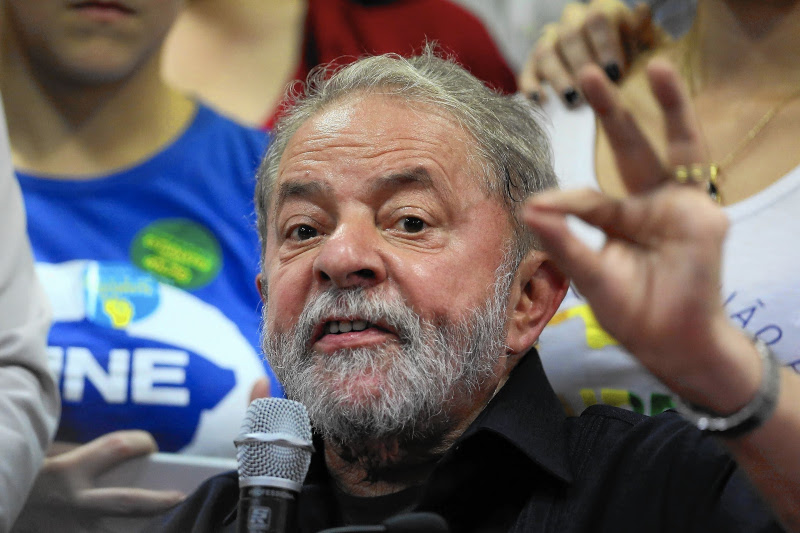

Pereira and Phillips are not even the most recent to lose their lives; Virgilio Trujillo Arana, a 38-year-old Indigenous Uwottuja leader was executed in Venezuela after receiving death threats related to his work protecting the Amazon. In Brazil, political violence has been on the rise leading up to the Presidential election this fall between far-right Jair Bolsonaro and former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known as Lula, from Brazil’s Worker’s Party.

The murders of Pereira and Phillips have brought renewed attention to the fight to defend the Amazon rainforest from profiteering interests of corporate agriculture, mining, and oil and gas, in addition to smaller-scale illegal fishing and hunting. While Brazilian authorities have painted the murders as a somewhat random act of violence, local Indigenous groups are claiming the victims were targeted by organized crime because of their work defending the Amazon.

Who are Phillips and Pereira?

Bruno Pereira had become somewhat well-known in Brazil for his work researching the Amazon and advocating for Indigenous rights and more robust protection of the region. In particular, Pereira led expeditions to the Javari Valley, the region with the highest concentration of isolated Indigenous Tribes, and he brought local Indigenous people together with the World Wildlife Fund on a project to digitally monitor the area against illegal activity. He was leading the largest expedition into the Javari Valley region in 20 years when he was removed from his position as the head of Brazil’s National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI) by officials in the Jair Bolsonaro administration.

Dom Phillips is a British journalist who had been visiting Brazil since the 1990’s and after writing about Brazilian DJs in the 2000s, he began working as a correspondent for The Guardian and the Washington Post, among others, and was focused on environmental topics by the late 2010s. His reporting for The Guardian on illegal deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has been nominated for numerous awards, but it also put him at odds with the Bolsonaro administration, because his reporting often highlighted the negative impacts of Bolsonaro’s pro-business policy regarding the Amazon.

Pereira and Phillips first ventured to the Javari Valley together in 2018 — the same year Bolsonaro ascended to power after former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was barred from running in the election due to corruption charges that were later thrown out when The Intercept discovered that the prosecution lawyers and Judge Sergio Moro conspired behind the scenes to secure a conviction. Lula has been released and is now leading Bolsonaro by 10 points in polls for the presidential election later this year.

How did they die?

With the political tide shifting, government officials, from local police to Bolsonaro himself, have tried to downplay the significance of Phillips and Pereira’s deaths and possible links to organized crime in the Amazon region. The bodies were discovered on June 15 when one of the suspects in police custody confessed and led the police to the site where Phillips and Pereira were buried. Despite the fact that police continue to make additional arrests related to the murder, the federal police claim there is no organized crime involved.

Brazil’s Vice President Hamilton Mourão has claimed Phillips was “collateral damage” in a killing targeting Pereira. Mourão implied that the attack was a random act of violence fueled by alcohol; “In my assessment, it must have happened on Sunday. On Sunday, Saturday, folks drink, they get drunk – the same happens here in the poorer areas, in the outskirts of the big cities,” he said.

The Indigenous organization UNIVAJA, however, cast doubt on the official narrative. “The cruelty of the crime makes clear that Pereira and Phillips crossed paths with a powerful criminal organization that tried at all costs to cover its tracks during the investigation,” said UNIVAJA in a statement.

UNIVAJA also wrote a letter elaborating on the organized crime operating in the Javari region that had formed a “composition of a gang of professional fishermen and hunters, linked to drug traffickers, who illegally enter our territories to extract our natural resources and sell them in neighboring municipalities. But measures were not taken fast enough. That is why today we are witnessing the murder of our partners.”

Brazil’s far-right president Jair Bolsonaro also deflected blame back to Phillips and Periera themselves, saying they were on an “adventure that wasn’t to be recommended.” Bolsonaro may be right were he pointing out of the dangers of land defenders in the Amazon, but his own policies are making the Amazon more dangerous and accelerating the destruction of the Amazon and its people.

In a statement, Greenpeace Brazil said the deaths were “a direct result of the agenda of President Jair Bolsonaro for the Amazon, which opens the way for predatory activities and crimes… in broad daylight.”

Patterns of Violence

For Indigenous people, protecting biodiversity on the frontlines of their communities has brought them face-to-face with the barrel of a gun throughout colonial history. In the Amazon Rainforest, the story has been especially bloody in the past several decades, as mining industries, agribusiness, illegal fishing and oil and gas have sought to operate further in the rainforest.

In December 1988, Chico Mendes was killed in the Amazon following his union activism and opposition to clearing the rainforest. Mendes has become a symbol for conservation in Brazil, but while his name is on government buildings, the government still cannot guarantee the safety of land defenders, Indigenous advocates and journalists.

Global Consequence

The deaths of Phillips and Pereira are a potential scandal for Bolsonaro at the time he faces an uphill battle to win re-election. On the issue of the Amazon, there is clear contrast between Bolsonaro, who has cheered on the development of the Amazon no matter the cost, and Lula, who as President was able to reduce deforestation while expanding the economy and has pledged that protecting the Amazon will be one of his top priorities if elected again.

“We will fight environmental crimes … and we will ensure protection of the rights and territories of Indigenous people against the advance of predatory activities,” said Lula while campaigning last month. The lead up to Brazil’s election on October 2, 2022 has come to include more fatal political violence when prominent union organizer and treasurer of Brazil’s Worker Party Marcel Arruda was shot at his own 50th birthday party by an off-duty police officer who shouted “Here is Bolsonaro” during the attack.

The stakes of the Brazil election are high for the entire planet. The Amazon deforestation rate for the first half of 2022 was 80% higher than the same period in 2018, with an estimated 1,500 square miles lost already this year. Fires have also continued to rage through the rainforest, with 2,500 hotspots recorded in June — a record for that month since 2007. Brazil’s role in managing the lungs of the planet is especially important right now because according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s most recent report, every 10th of a degree of warming will make a difference in humanity’s ability to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

For now, the Indigenous people of Brazil continue to fight back, and have called on international supporters to boycott Brazilian deforestation products. In response to recent events, Indigenous Land Defenders have led protests calling for stronger protections of their home and a thorough investigation of the murders of Pereira and Phillips. Kura Kanamari, a leader from the Kanamari people from the Javari Valley Indigenous territory, told demonstrators in Atalia Do Norte, a town near the Javari Valley, “We don’t want war with anyone. All we want is our peace and for our lands to be respected because our supermarket is in the lakes, the land and the forests. If this is all destroyed, our isolated relatives will go hungry.”