At the end of February 2022, Russian forces started an invasion of Ukraine. In terms of the number of troops and weapons on the ground, it is now the largest military conflict on the European continent since World War 2.

As we all watch the horror unfolding in Ukraine, the convenient narrative that Russian President Vladimir Putin is an unhinged maniacal dictator hellbent on taking over Europe has come to dominate much mainstream news coverage, at least in the United States. U.S. President Biden recently delivered his State of the Union address and saw his approval rating shoot up eight points, so it seems Americans are finally putting aside some partisan vitriol and uniting behind the flag – the Ukrainian flag that is.

It is common for Western media to frame Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as defending democracy against Putin – a shadowy, even Hitler-like figure – but that narrative is an enormous and dangerous oversimplification that masks the important details of the war in Ukraine, which has been going on since 2014. Those details reveal the true causes of the war: one, the internal conflict of Ukraine’s people who are culturally caught between identifying more with Russian or European society; two, the external political conflict between NATO member states and Russia, with both sides vying for influence within Ukraine; and last, but certainly not least, the conflict of who will meet Europe’s energy needs and who will control the massive oil and gas reserves that were discovered in Ukraine just a few years before the onset of war.

Russia & Nord Stream 2

Russia is among the top three oil-producing nations in the world, with Russia, the United States and Saudi Arabia in a league of their own in terms of oil and LNG (liquified natural gas) exports. The Russian economy depends on its oil and gas exports, which account for about 60% of total Russian exports. Russia sells oil and gas to its neighbors in Western Europe as well as Asia, and even the United States which imports about 600,000 barrels per day of Russian oil.

Europe has become dependent on Russian gas, especially countries in Eastern Europe as well as Germany and Italy. In 2021, 38% of the cumulative gas imported by countries in the European Union came from Russia. All of that gas is getting to Europe by pipelines, and for a long time after the fall of the Soviet Union, the only route for the pipelines was through Ukraine.

Although Russia has since built pipelines bypassing Ukraine, Nord Stream 2 is the most significant. Intended to carry 3.9 trillion cubic feet of LNG per year across the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany, Nord Stream 2 was completed last September despite concerns from both U.S. Presidents Biden and Trump, who found themselves on the same side of this issue and in the company of Yuriy Vitrenko, the CEO of Ukraine’s large state-owned natural gas company Naftogaz (more on them later).

The opposition to Nord Stream 2 was seemingly all about ensuring that Russia did not have too much control over Europe’s energy supply. Publicly, U.S. officials have said that Russia could weaponize the threat of turning off Europe’s energy. But as is often the case with the fossil fuel industry, power struggles framed around national or regional security are often equally, if not more, about who gets to profit from oil and gas. While on the surface, the recent escalation of violence can be seen as a reckless, even desperate act by Vladimir Putin, the war in Ukraine has always been about controlling Europe’s energy supply as much as it is about a cultural and political conflict within Ukraine.

Ukraine’s fossil fuel reserves

It has been estimated that Ukraine’s natural gas reserves measure more than 1 trillion cubic meters, making them either the second or third largest reserves in Europe. In the early 2010s, geologic surveys began to reveal the extent of Ukraine’s oil and gas reserves, and investment from the European & American fossil fuel industry soon followed in 2012 with Shell and Chevron partnering with Ukraine to begin extracting the gas.

These discoveries were concentrated in three main regions of Ukraine: one near Lviv in the West, one in the eastern Donetsk region, and the largest in Ukraine’s exclusive economic zone in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov off the coast of Crimea. In Crimea, Exxon Mobil had outbid a Russian gas company for the $735 million contract to drill offshore wells.

Crimea and Donetsk

When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, it was a direct blow to Exxon and Ukraine’s fossil fuel industry. After voting to secede from Ukraine, the Crimean parliament also voted to nationalize Chornomorneftegaz, a subsidiary of Naftogaz that was headquartered in Crimea and had been investing in the infrastructure to extract gas. Crimea then sold Chornomorneftegaz to Gazprom, Russia’s biggest fossil fuel company, essentially handing Russia the keys to the Black Sea gas reserves.

The Donetsk gas reserves are also central to the conflict, as they are located in and along the region currently controlled by Russian-backed separatists. Here is where Ukraine’s rampant corruption becomes most obvious. In March 2014, Ukrainian-Israeli billionaire Igor Kolomoyskyi was appointed governor of the province neighboring Donetsk. Kolomoyskyi’s business empire then included major holdings in the fossil fuel industry, including Ukrnafta, the largest extractor of oil and gas in Ukraine.

Kolomoyskyi then proceeded to use his own wealth to fund a private army – including several Nazi militias – to fight the separatists. According to The Guardian, Kolomoyskyi offered a $10,000 bounty for any captured Russian “saboteur,” with additional bounties for any weapons recovered. Kolomoyskyi is also accused by the U.S. Department of Justice of laundering billions of dollars through his banking empire, and he would go on to play a pivotal role in the rise of now-President Volodymir Zelensky.

After a dramatic public spat with Ukrainian President Poroshenko, Kolomoyskyi was pushed out of Ukrnafta and his bank Privat Group – Ukraine’s largest – was nationalized in 2016. Not long after, Kolomoyskyi used his major media outlet 1+1 to broadcast the fictional drama “Servant of the People,” which featured the actor Volodymir Zelensky’s dramatic journey from being a charismatic everyman to rooting out corruption by becoming the fictional President of Ukraine. Zelensky’s fictional presidency on Kolomoyskyi’s TV channel became the launching pad for a new “Servant of the People” political party and Zelensky’s actual presidential campaign, which was also backed by the oil magnate. Kolomoyskyi equipped Zelensky’s campaign with its official vehicle, primary lawyer, and extensive financial support – the latter of which was controversially revealed to have occurred through offshore money laundering, as disclosed in the Pandora Papers leak.

Of course, we cannot leave out the most famous Ukrainian fossil fuel company, Burisma, which became well-known because Joe Biden’s son Hunter sat on its board of directors from 2014 to 2019. As a holdings company, Burisma has over a dozen subsidiaries, mostly fracking companies. Burisma’s goal seems to have been to open up the Ukrainian market to more European and American investment by softening Ukraine’s reputation for corruption. In addition to offering board seats to Biden, the former Polish President and a former top CIA operative, Burisma also founded an annual Energy Security Forum which featured prominent German and American government officials, according to the International Policy Digest.

Ukraine’s economy was becoming more closely associated with the European Union, where the gas market was wide open to challenge Russia’s dominance. For strategic reasons, the U.S. also supports Ukraine as an alternative petro-state to Russia. But as much as Ukraine’s economy could integrate with the West, that does not guarantee any military protection from the United States or Western Europe.

NATO: What is it?

The final step to integrate Ukraine with the United States and European powers would be admitting Ukraine into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Commonly referred to as NATO, it is essentially a military alliance between the U.S., Canada and many European countries. Formed in 1949, its stated purpose was to counter the influence of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact alliance.

In pursuit of this goal, the CIA secretly recruited and rehabilitated hundreds of Nazi generals and intelligence officers to form the Gehlen Organization – a Nazi spy network operating on behalf of NATO, especially in Eastern Europe. For decades, NATO’s top leadership was openly filled with many of Nazi Germany’s highest-ranking and decorated military officers.

All members of NATO are bound to Article 5 of the North Atlantic treaty, which states that if a single NATO country is attacked, all other members must come to its defense. This article makes NATO an attractive organization for small countries that have nowhere near the military might of the United States because as members, they know the U.S. military will back them up if they are attacked. The downside for the U.S. is that it could get drawn into a war.

NATO, however, is not a merely defensive alliance; NATO forces have mostly been involved in military campaigns when no NATO country was directly attacked. In the 1990s, NATO enforced a no-fly zone in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Around the end of the decade, NATO was criticized by human rights groups for bombing a large number of civilians in Yugoslavia.

In the 2000s, NATO forces invaded both Iraq and Afghanistan, killing over two million civilians in their occupation of these countries. After the United States and Britain, Ukraine was the third-largest contributor of soldiers to the invasion and occupation of Iraq – perhaps in an effort to prove their worth to NATO allies, despite not being a member.

In 2011, NATO enforced a no-fly zone in Libya, using an extensive campaign of airstrikes to overthrow the Libyan Jamahiriya led by Muammar Al-Gaddafi, and plunging the country into a decade of civil war while backing militants who used the regime change to establish widespread anti-black slave markets.

NATO Expansion

When the Soviet Union was broken up in 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev claimed that the United States promised that NATO would not extend eastward beyond Germany. Former U.S. diplomats have confirmed that the U.S. and other member states had made this verbal assurance to the Soviets, and hundreds of recently declassified documents have verified this promise. Within a few years, however, NATO’s stance had changed, leading experienced U.S. diplomat George Kennan to conclude in 1997, “expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era.”

In the two and a half decades since Kennan’s warning, NATO has nearly doubled from 16 to 30 member states. After receiving invitations in 2002, Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia became members of NATO in 2004, bringing the alliance to Russia’s border. Also in 2002, the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan was written detailing various changes Ukraine’s government must make in order to be considered to join NATO.

By 2008, NATO signaled that Ukraine had met the objectives of the action plan, and NATO was ready for Ukraine to join. But there was one big problem; Viktor Yanukovych was elected in 2010, and after promising on the campaign trail to keep Ukraine out of NATO, he signed a law affirming Ukraine’s neutral status in July 2010.

Euromaidan

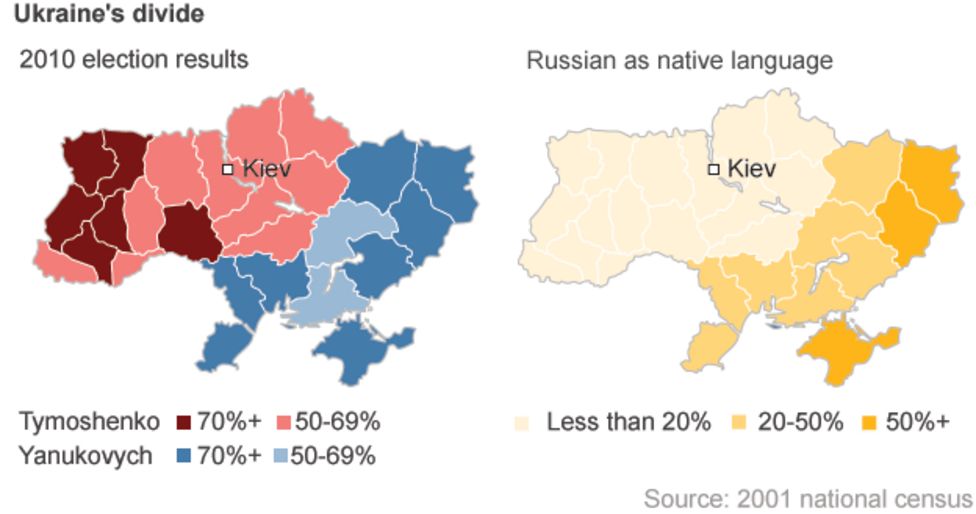

Yanukovych won a contested 2010 election against rival Yulia Tymoshenko who favored closer ties with NATO countries, while Yanukovych was allegedly controlled by Moscow. Both candidates accused each other of attempting to rig the results. In the end, the official result is that Yanukovych edged out Tymoshenko by more than 800,000 votes, with Yanukovuch’s strongest support coming from the Donbass region of Eastern Ukraine.

In 2013, Yankovych pulled Ukraine out of a major agreement that would have further integrated Ukraine’s economy with that of the European Union and laid the groundwork for Ukraine to eventually be allowed in the EU and NATO. Instead of signing the agreement, Yanukovych began negotiating with Moscow – a decision that angered many Ukrainians and the governments of the EU and NATO members.

Protests began in November 2013 against corruption in the government and Yanukovych’s rejection of the European Union. These soon evolved into sustained civil unrest centered at the Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The bloody upheaval and replacement of Ukraine’s government, in which Yanukovych eventually fled the country, became known as the Euromaidan Revolution. Although it is often framed as a clear-cut victory of the will of the people to bring about a democratic government, there have always been questions about key U.S. officials’ involvement in what took place.

Foreign Intervention?

During the middle of the unrest, leaked audio emerged of U.S. diplomats on January 28th, 2014, discussing who should replace Yanukovych. Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland was recorded speaking with the U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt, in which they decided that Arseniy Yatsenyuk was best suited to help lead the new government. About a month later, on February 27th, Yatsenyuk became Prime Minister, and Petro Poroshenko would later become President.

The leaked audio of Nuland is not the only evidence of U.S. involvement in Ukraine’s internal power struggle, according to a timeline compiled in CounterPunch. For example, months earlier, Nuland spoke at the International Business Conference sponsored by Chevron, in which she said that since 1991, the U.S. had invested $5 billion in the “development of democratic institutions” in Ukraine to help the country achieve its “European aspirations.”

We do not know the full extent to which the U.S. State Dept. or intelligence agencies may have been involved behind the scenes, but it is clear that Yanukovych’s opposition had the full public support of the United States and many other NATO member states. Journalism which explores this question is being increasingly censored by companies such as Google, which recently removed Oliver Stone’s 2016 Documentary Ukraine on Fire from YouTube.

Neo-Nazi forces

Nuland was not the only U.S. government official to make a trip to Ukraine, and in the process of bolstering Yanukovych’s opposition, the U.S. also became involved with some of Ukraine’s extreme right-wing parties and militias. In 2013, U.S. Senator John McCain visited Kyiv to tell the crowds “Ukraine will make Europe better and Europe will make Ukraine better.” McCain shared the stage with Oleh Tyahnybok, founder of Ukraine’s Svoboda party, the socialist-nationalist party which has its roots in Neo-Nazi ideology and iconography.

Tyahnybok became one of the leaders of the opposition to Yanukovych, and he was not the only opposition leader with Neo-Nazi ties. The most well-known far-right militia in Ukraine, the Azov Battalion, played a crucial role in the street protests that led to ousting Yanukovych, and they went on to lead the fight against separatists from Eastern Ukraine. The Azov Battalion became an official part of Ukraine’s National Guard in 2015, and was given a building by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense to house their training, recruitment, and fascist literature – according to a report by Time Magazine from 2021. Currently, Azov is a major part of Ukraine’s efforts to enlist and train civilians in the fight against Russia.

Hate crimes committed by Nazis working for the Ukrainian government are well-documented, such as the anti-Roma pogrom committed by the Nazi C14 militia deputized by Kyiv’s city government in 2018. Even recently amidst increased media attention, the Ukrainian National Guard tweeted a video glorifying a national guardsman in the Azov battalion who was greasing his bullets with pig fat and referring to Muslim soldiers in the Russian army as “Kadyrov Orcs.”

The U.S., its allies, and these Neo-Nazi militias did not just happen to share the common goal of overthrowing Yanukovych. Through military aid, the U.S. and its allies have actively and continuously provided them with weapons and funding. And this is deliberate: in late 2015, the Pentagon killed an amendment which had passed the House and would have prevented the U.S. soldiers training the Ukrainian military and national guard from continuing to work with Nazi battalions. Understandably, this support by the United States and its allies has not sat well with many Jewish communities, and in 2018, a group of human rights activists also petitioned Israel to stop arming Neo-Nazis in Ukraine.

The War: Donbass and Crimea

Leading up to the 2014 regime change, Ukrainians were already divided, with many people in the East having deeper ties with Russia. Data reported in the BBC from the Ukraine census shows that nearly 60% of Crimea’s population identified as ethnically Russian in 2001. Another survey in 2004 showed that more than 97% of the people in Crimea, as well as 93% and 89% respectively in the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk, speak Russian as their native language. The rest of Eastern Ukraine had between 20 and 50% native Russian speakers.

These ethnic and linguistic divides translated to political divides as well. The 2010 electoral results map correlates nearly perfectly to the map of Ukraine’s native-Russian-speaking population, with Yanukovych’s support strongest along Ukraine’s eastern and southern edges, and Tymoshenko’s support strongest on Ukraine’s western border.

Ukraine was primed for internal conflict over integration with Europe. After the pro-European side came out ahead in the Euromaidan Revolution with U.S. support, it was Russia’s turn to make their move. Russia had many reasons it might have wanted to take Crimea: securing fossil fuel reserves for economic interests, seizing a key strategic port in the Black Sea and incorporating a majority-ethnically Russian region with the motherland among them. Russia invaded and annexed Crimea in February and March 2014, and the war was on from there.

After Russian forces invaded, the question of becoming part of Russia was brought to the people of Crimea in a referendum on annexation. The official results of a referendum is that 95.5% voted to become part of Russia, with 83% turnout for the vote. The referendum, however, has been criticized for the fact that Russian soldiers were occupying Crimea at the time of the vote, and politicians from the Muslim minority Crimean Tatars, who are members of Ukraine’s pro-European integration party, called on their constituents to boycott the vote. The validity of the results has always been questioned, especially after evidence emerged that allegedly showed a much lower turnout estimate.

Following Russia’s swift takeover of Crimea, most of the armed conflict leading up to 2022 took place in the Donbass region of Eastern Ukraine which encompasses the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. From the start of the conflict between Ukraine’s armed forces and Neo-Nazi militias on the one side, and the Russian-backed separatists on the other, both sides have accused the other of committing war crimes including execution-style killings of enemy soldiers.

In late 2014, Human Rights Watch concluded that Ukraine had indiscriminately targeted civilians in populated areas of Donetsk with cluster munitions, which could constitute a war crime. Ukraine, along with Russia and the United States are among the minority of countries that did not sign the 2008 treaty banning cluster munitions. As of October 2021, there have been more than 13,000 casualties in the Donbas region, including more than 3000 civilians, about 4200 Ukrainian soldiers and 5800 separatist soldiers, according to the United Nations.

Rival Military Drills

While this war was going on, Ukraine’s new government sought to make good on the promise to bring the country closer with the West, militarily. In 2019, Ukraine amended their constitution in an effort to bind the nation to a “strategic course” of eventual membership in the European Union and NATO, emphasizing the “irreversibility of Ukraine’s European and Euro-Atlantic course.” That amendment enshrined Ukraine’s intent to join NATO and set in motion further collaboration between Ukraine’s armed forces and the militaries of various NATO member states.

The following year, 2020, Ukraine and NATO allies held a military drill in the Black Sea with NATO allies in July and another drill on land near Crimea. In February 2021, Ukraine and NATO announced that they would be holding eight joint military drills on Ukrainian soil over the course of the year. The drills gave Russia a preview of what Ukraine’s membership in NATO could mean.

At the tail end of March 2021, news first emerged about a growing number of troops along the Russia-Ukraine border. Russia said that they feared Ukraine’s armed forces were about to reignite conflict in the Donbass region, according to Reuters. Ukraine’s official position is that the separatists were the ones who broke the ceasefire first.

Over the month of April, while Russia continued to amass troops near its border, NATO countries condemned and sanctioned Russia, and they also began more military drills with Ukraine. Zelensky asked NATO again to admit Ukraine. Tensions continued to rise as sanctions hit the Russian people, and many Russian diplomats were expelled from the U.S. and Ukraine, and vice versa.

The potential for active fighting grew over a tense summer 2021, when Russia reportedly fired warning shots at a UK warship in the Black Sea off the Crimean coast. Every few weeks, Ukraine would practice military drills joined by various NATO allies, and Russia would practice military drills, sometimes joined by Belarus or even by China – each framed as a response to the last provocation. Russia repeatedly warned the world that Ukraine joining NATO would be a “red line,” and NATO officials still would neither dismiss nor commit to Ukraine gaining membership.

Controversial Canals and Pipelines

All the while, Ukraine had been causing water shortages in Crimea by blocking a canal that supplies 85% of Crimea’s drinking water. Crimea’s capital city was forced to implement daily shutoffs starting in February 2020, as Crimea’s reservoirs had become depleted after drought linked to climate change and 6 years without a recharge from the canal. In July 2021, Russia took the issue to international court, alleging Ukraine is violating human rights. One of Russia’s first military maneuvers in its February 2022 invasion was to destroy the dam blocking the canal.

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline finished construction in September 2021, and just needed to be turned on. This was a point of contention between the U.S. and Germany, as the U.S. put on another round of sanctions related to the pipeline, but Germany still wanted to buy LNG from Russia. The one point where German and U.S. diplomats agreed was on the fact that if Russia invaded Ukraine, the pipeline deal would be off.

Failed Diplomacy

In early February 2022, the conflict took on more urgency, as U.S. intelligence warned that Russia was planning to go on the offensive in Ukraine. Initially, European powers and even Ukraine’s Zelensky voiced skepticism that Russia would launch an invasion. With Russia and the U.S. having expelled each other’s diplomats, French President Emmanuel Macron had become an important broker between Washington and Moscow, and he finally managed to get U.S. Secretary of State Tony Blinken and Russian Foreign Secretary Sergei Lavrov to agree to a meeting in late February, with the possibility for a Biden-Putin summit on the table.

Scarcely a week before the peace talks were set to begin, an unusually intense round of shelling shook the Donbass with both Ukraine and the Separatist Republics blaming each other for the violence. In the wake of the renewed warfare, more than 60,000 Russian-speaking residents of Donetsk and Luhansk fled the Donbass seeking refuge in Russia, and U.S. intelligence predicted Russian military intervention was imminent.

Following the resurgence of war in the Donbass, Vladimir Putin delivered a speech that significantly raised the stakes. He officially recognized the independence of the separatist territories of Donetsk and Luhansk as sovereign republics. He announced that Russian troops would move into the republics as peacekeeping forces in a special military operation. He also listed his demands which included demilitarizing Ukraine, purging the Nazi influence from Ukraine government and armed forces, and guaranteeing that Ukraine would not join NATO.

After this speech, U.S. Secretary Blinken called off the meeting with Lavrov. Under clear pressure from the U.S., German Chancellor Olaf Sholtz announced that Nord Stream 2 would no longer be approved. In the days immediately following these events, Russia went beyond an isolated mission in the Donbass region and began to invade Ukraine from the east, as well as the south through Crimea and north through Belarus.

Climate Complications

Another factor contributing to the failure of diplomacy may have been the interests of the U.S. fossil fuel industry. Even before the war escalated in February 2022, the U.S. refusal to accept any of Russia’s diplomatic conditions, such as Ukraine remaining neutral outside of NATO, was proving highly profitable for American fossil fuel oligarchs, according to a report in Bail Out Watch. The top 18 Big Oil CEOs had already seen their net-worth grow by billions since Joe Biden took office, and many of them proceeded to cash out on stock gains once Biden declared the war was inevitable. The U.S. fossil fuel industry also stands to profit from the cancellation of Nord Stream 2, as it promotes increased U.S. fracking for gas as a “powerful weapon against Russia” and profitable means of capturing the newly available European market share.

Although it is not the only factor, the war in Ukraine is clearly about a pipeline, and the question of who will deliver gas to Europe. In addition to expressing outrage over Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its massive offshore oil and gas reserves, Ukraine was very opposed to Nord Stream 2 because it allowed more Russian gas to bypass pipelines that flow through Ukraine, where they charge transfer fees. Ukraine’s Naftogaz company was in the red by about $700 million and was looking for a major bailout from the International Monetary Fund, which had been financing Ukraine’s fossil fuel industry for several years.

With Naftogaz, a majority state-owned company, in such trouble, and Ukraine about to lose the upper hand if Nord Stream 2 went into operation, Ukraine had a major financial incentive to stop Nord Stream 2 by any means necessary. Russia, on the other hand, had invested heavily in Nord Stream 2 as a way to secure its position in the European energy market for decades to come, and when the project was canceled, the Russian government may have felt that it had nothing left to lose by fully invading Ukraine.

IPCC’s Warning

Only a week after the invasion began, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, issued a report that shows the total disaster of waging war over fossil fuels. The report demonstrates that about 3.5 billion people’s lives are already affected by the climate crisis, and every tenth of a degree of warming matters to prevent the worst effects of climate change – many such effects will be irreversible.

With such slim margins between humanity’s ability either to stop the worst effects of climate change or dive headfirst toward worst-case scenario climate collapse, the war in Ukraine should highlight the need to rapidly abandon fossil fuels for other sources of energy. But unfortunately, war is likely to make the problem worse. The United States military, should it get further involved, is the worst carbon polluter on the planet, but sustained Russian and Ukrainian military activity alone will have a detrimental effect on the environment in addition to the devastating loss of human life.

The war has also launched gas prices to record highs, especially after the U.S. banned imports of Russian oil and gas. High prices are saving the U.S. fracking industry, which was already in trouble before the pandemic. COVID-19 lockdowns brought gas prices to record lows, so now the fossil fuel industry is finally getting a lifeline to make back the lost profit. Although high prices may cause renewables to be more attractive in the long term, in the short term, they boost fossil fuel industry profits.

No-fly Zone

As the conflict escalated, protests immediately popped up around the world on a scale not seen since the 2020 protests after George Floyd’s death or the pre-pandemic global climate strikes in 2019. Stopping war, unjust death, and saving the planet are all issues that inspire major amounts of energy and organizing globally. Many of the latest protests about the war in Ukraine, however, have inadvertently been pro-war, as #StandWithUkraine has predominantly supported President Zelensky amidst his repeated calls for a no-fly zone.

Demonstrations across the U.S. increasingly are organized around asking NATO to enforce a no-fly zone over Ukraine. In Chicago, thousands of protesters chanted, “close the sky,” and at New York City’s Guggenheim Museum, an artist display launched hundreds of paper airplanes to ask for a no-fly zone. Although Secretary Blinken has voiced that at this time, the U.S. will not implement a no-fly zone, polling shows that a majority of both Democratic and Republican voters currently support a no-fly zone.

A no-fly zone, however, could easily escalate even further to a hot war between NATO allies and Russia. It would require NATO to shoot down any Russian or Belarusian jets that try to enter Ukrainian airspace. In order to even have that capability, NATO may have to strike anti-air missile systems in Russia to allow NATO ally aircraft to patrol the skies. There is a very serious risk that a no-fly zone will trigger World War 3.

An Anti-War, Pro-Climate solidarity movement

The fervent energy behind #StandWithUkraine is being driven by around-the-clock western media coverage of the war – often framing Putin as a maniacal dictator with no rationale for invasion and Zelensky as the defender of freedom and democracy, the only leader standing between the forces of Evil and the West.

Most Western media, however, is not giving proportional attention to the ongoing humanitarian crises in Yemen or Afghanistan, where U.S. military and economic aggression has caused millions of civilian deaths, and continues to cause enormous suffering today from sanctions and starvation. In fact, there have been numerous examples of racist coverage in mainstream media expressing horror that war would afflict Europeans with “blonde hair and blue eyes,” while normalizing decades of war in Africa and the Middle East as “expected.”

In more ways than one, the media coverage of Ukraine has been highly skewed. Mass media in the U.S., including mainstream news sources as well as tech companies like Google and Meta, are attempting to whitewash the current Ukrainian government’s integration of Neo-Nazi battalions in its military and national guard, while also obscuring the role of NATO military provocations and fossil-fuel dependence at the heart of the conflict. The result is to exploit the suffering of Ukrainians and blame it exclusively on Russia in order to manufacture consent for a U.S. and NATO-backed war against Russia in Ukraine.

This media narrative steps to the drumbeat of war – with Russophobia explicitly allowed and even officially promoted, and dissenting media increasingly banned by American big tech companies. Meanwhile, in the name of supposedly stopping the next Hitler, the U.S. government is accelerating its shipments of money and weapons to actual Neo-Nazis. Without a real anti-war movement and a vigilant media willing to highlight these underreported elements of the conflict, pro-war propaganda has no real competition.

The violence will not stop unless we choose to stand for true peace for all people and for the planet. The current anti-war movement needs to understand that ending fossil fuel dependence is essential to preventing war, and the climate action movement needs to understand that more war will lead to climate collapse. Additionally – and especially from within the Western media ecosystem – it is imperative for both movements to seek knowledge beyond Western militaristic propaganda. To find enduring solutions, we must see war in its true historical and ecological context. That is as true in Ukraine as it is in Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Tigray and every other region of the world.