Hundreds of protesters led by a coalition of Indigenous youth activists and environmental organizations marched around Washington, D.C. on Thursday, April 1st, carrying a 320-foot long black snake. The snake is a direct reference to an ancient Lakota prophecy and symbolizes fossil fuel pipelines, such as the Dakota Access Pipeline, DAPL, and the Enbridge Line 3 pipeline, which is currently under construction despite the outcry of Indigenous Nations and water protectors. The protesters advocated for these pipelines to be shut down and stopped, in addition to the Mountain Valley Pipeline and Enbridge Line 5 pipeline.

The crowd of several hundred marched to the Army Corps of Engineers office where they staged a “die-in” protest before moving to Black Lives Matter Plaza outside the White House where the Indigenous Youth symbolically killed the black snake.

Another view of the giant snake and the dozens hoisting it, departing from the corps headquarters and marching under the Chinatown arch earlier. Written on its side:

Biden: stop the black snake

Shut down DAPL (Dakota access pipeline)

Stop Line 3 pic.twitter.com/0JmthpnvQk— Alejandro Alvarez (@aletweetsnews) April 1, 2021

Along the way, protesters chanted “Water is life,” “Can’t drink oil; keep it in the soil” and demanded that the Biden administration “Build Back Fossil Free.” The protest comes the same week that President Biden, whose campaign slogan was “Build Back Better,” has released a plan to invest $2 trillion in infrastructure over ten years.

One of Biden’s first executive orders was to cancel the Keystone XL Pipeline, which had been canceled by President Obama before the Trump administration reversed that decision. A poster for the protest put out by the group Rezpect Our Water reads, “We’re giving the fossil fuel snake back to D.C,” and also calls on President Biden to revoke the permits for DAPL and the Enbridge Line 3 pipeline. At the end of January, more than 250 individuals and groups, including prominent politicians, recording artists and celebrities, signed a letter to President Joseph R. Biden urging him to cancel the permits for Line 3 and DAPL.

The protestors made up of members of the Standing Rock Youth, the Cheyenne River Grassroots Collective, and many other frontline water protectors from the Lakota, Anishinaabe and Standing Rock Sioux tribes, among others, danced and sang songs in front of the White House after destroying the fossil fuel snake. There were speakers at Black Lives Matter Plaza as well as at the Army Corps of Engineers Building who emphasized the importance of protecting water and respecting the rights of Indigenous People.

“Through our wild rice beds, through our rivers, through our waters, through the headwaters of the Mississippi River, that’s where these guys want to send Tar Sands [Oil] from Alberta to the shore of Lake Superior. It’s madness and it just keeps on going,” Ojibwe activist and founder of Giniw Collective Tara Houska told the crowd outside the Army Corps of Engineers office. “They should have done the right thing in the first place which is respecting Indigenous Sovereignty, respecting when we say no. We are nations that existed before this country and we still exist today.”

Enbridge Line 3 Pipeline

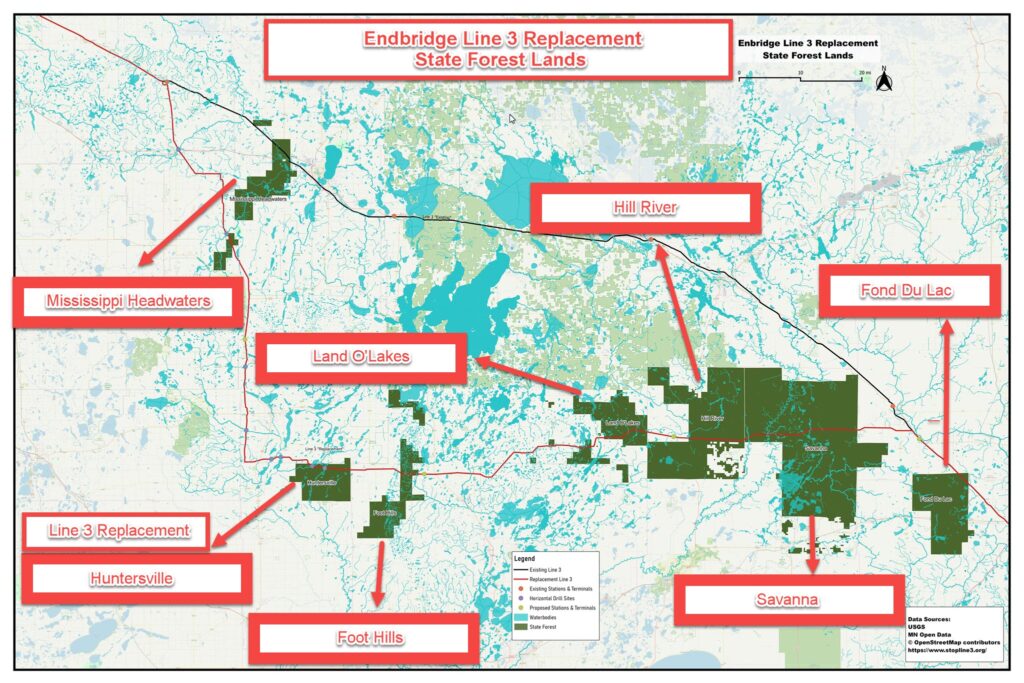

Canadian energy company Enbridge advertises its Line 3 pipeline as a replacement of an existing pipeline. The project, however, would cut through the treaty territory of the Anishinaabe people, home to their best lakes and wild rice watersheds which make up an integral Anishinaabe agroecosystem. Furthermore, if completed, the new Line 3 would transport nearly twice the volume of Canadian tar sands oil as the current pipeline. The 36-inch wide pipe is proposed to run from Hardisty in Alberta, Canada all the way to Superior, Wisconsin, passing through North Dakota and Minnesota along the way.

Today, the North Dakota and Wisconsin sections of Line 3 have been finished, but Enbridge has run into fierce resistance in Minnesota where construction began in late 2020. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers granted Enbridge permits to discharge industrial wastewater as a byproduct of construction directly into federally protected rivers and streams, clearing the final hurdle for Enbridge to begin construction in November.

In December, the Red Lake Band of Chippewa, White Lake Band of Ojibwe, and environmental groups Sierra Club and Honor the Earth filed a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers, arguing that the permit was granted without a sufficient Environmental Impact Statement to evaluate the damage of a potential oil spill or the pipeline’s impact on climate change. The suit also alleges that Enbridge and the Army Corps of Engineers failed to gain the consent of the tribes in violation of tribal rights and treaties. A similar lawsuit filed in January by the group Friends of the Headwaters argues that the Army Corps of Engineers failed to assess the impact of pollution on the Mississippi River Watershed and Lake Superior.

“Water is life”

Opponents of the Line 3 pipeline do have reason to worry about its impact, especially when it comes to water pollution. The proposed pipeline route crosses more than 200 bodies of water and about 800 wetlands in northern Minnesota alone, according to a report in Minnesota Public Radio. Many of these lakes, streams and wetlands comprise the headwaters of the Mississippi River, a critical source of fresh water for wildlife, drinking water and agriculture – including those which have supported the wild rice culture of the Anishinaabe for thousands of years.

Not only would an oil spill put the Mississippi River at significant risk of pollution, but a spill from Line 3 could also pollute the water of the Great Lakes. In 1962 and ’63 multiple oil spills dumped a combined 3.5 million gallons of oil into the Mississippi River, in an event that devastated wildlife and water quality and led to the creation of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. For comparison, the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico spewed about 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, killed more than 100,000 animals and still impacts the Gulf ecosystem today.

If completed, the Line 3 pipeline would carry nearly 32 million gallons, or 760,000 barrels, of oil per day across the Mississippi headwaters. The worst-case scenario of an oil spill from the Line 3 pipeline would be an absolute tragedy for the ecosystem and humans who rely on clean water. Enbridge says that the Line 3 project is necessary, however, to replace the original Line 3 that was built in the 1960s, and ensure that it has the most up-to-date safety standards. The company does not mention how long the new pipeline will last before it needs replacement.

Tar Sands Oil

In addition to water pollution, the other major environmental concern around Line 3, and pipelines in general, is that it will prolong dependence on fossil fuels and worsen the ongoing climate crisis. The greenhouse gases that are emitted when oil is burned are heating up the earth, causing extreme weather events and loss of glaciers and polar ice caps. Of all the oil fields in the world, perhaps none are as rich or as dirty as the Tar Sands Oil Field located in Alberta, Canada.

The Tar Sands of Alberta contain an estimated 12% of global oil reserves, and the Tar Sands oil is an especially heavy, thick variety known as bitumen. Extracting the bitumen creates vast toxic ponds visible from space that poison wildlife and threaten the local watershed. To get the oil to consumers, pipeline companies come in and Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline is only one such pipeline; heading west through Canada, the Canadian Royal Mounted Patrol, CRMP, has brutalized Wet’suwet’en Land Defenders in order to clear the way for the Coastal Gaslink pipeline to be built on unceded Wet’suwet’en land without the consent of the hereditary chiefs.

The local environmental and social impacts of tar sands extraction are severe; furthermore, it is not an exaggeration to say that continuing to extract and burn tar sands oil threatens the entire planet. Climate scientist James Hansen, who first testified to the U.S. Congress about the dangers of greenhouse gases and climate change in 1988, recently warned that burning the tar sands deposits would be “Game Over for the Climate.”

The tar sands contain an estimated 170 billion barrels of crude oil, according to an EJOLT report. Bitumen is about 31% dirtier in terms of greenhouse gas emissions than other forms of fossil fuel, so Hansen estimates that turning to tar sands reserves will ultimately raise global CO2 concentration above 500 parts per million, or ppm. Currently, the atmosphere is at about 421 ppm, but scientists believe we need to stay at or below 350 ppm to avoid the most adverse effects of climate change: uninhabitable heat, sea-level rise, more frequent extreme weather events, and full-on climate collapse.

Harassment and Trafficking

In addition to the likely future impact on the environment, the construction of pipelines like Enbridge’s Line 3 also has an immediate impact on the community. From the perspective of Enbridge, the short-term impacts are overwhelmingly positive; according to the company, the project will create 8,600 jobs, 6,500 of which will be for locals, over two years. It is not clear, however, that any of these jobs will remain after construction is complete. Enridge also says that only 50% of the payroll will go to locals, suggesting that all the highly paid positions will be hired from outside Minnesota.

Behind these numbers about job creation, however, is a much darker story about the impact of bringing thousands of construction workers to rural camps. A bombshell report in Truthout details the increase in sexual assault, harassment and allegations of sex trafficking in northern Minnesota since the arrival of the Enbridge construction workers. So far, two pipeline workers have been charged with soliciting sex from a minor.

Although Enbridge does have mandatory training on sexual harassment and sex trafficking, according to Truthout, these consist of only 20-minute awareness videos with no test or discussion. And while Enbridge claims to take the issue very seriously, they have yet to provide compensation after the Violence Intervention Project based in Thief River Falls, MN requested reimbursement for hotel rooms they purchased to shelter at least two additional women who say they were assaulted by pipeline workers.

Because the Line 3 pipeline is being built on and near Indigenous communities, the victims of sexual harassment and violence are predominantly Indigenous women and girls. This is a systemic crisis taking place around pipeline man-camps across the continent, which even the Canadian government has explicitly recognized as an ongoing genocide.

The Spirit of the Buffalo

With neither Enbridge nor the opponents of the Line 3 pipeline willing to back down, militarized police have increasingly been called in to support Enbridge clearing Indigenous protesters from their own land. In February, The Intercept reported that Beltrami County Minnesota had requested a $72,000 reimbursement from Enbridge for riot gear including tear gas, pepper spray and bean bag bullets, claiming on the invoice that the riot gear is personal protective equipment, or PPE. So far, Beltrami County has been reimbursed $170,522 for its efforts to clear the way for Enbridge to build the Line 3 pipeline.

The pipeline opponents may face an uphill battle, but the resilience of Indigenous communities has been built up throughout hundreds of years of oppression. Last year, Branch Out interviewed Geraldine McManus, a Dakota two-spirit organizer and founder of the Spirit of the Buffalo camp that stood in the way of Enbridge’s Line 3 route outside Gretna, Manitoba, near the border between Canada and North Dakota.

“No matter how we gotta do it we get it done and we put our lives on the line. Many people put their lives on the line, and nowadays it seems that’s what we have to do,” McManus told Branch Out about the sacrifice Indigenous people make to protect the Earth.

“We need to be creative, we need to be inventive, and we need to have some kind of economic basis because out there in the world, right. Look who we’re up against. They’re billionaires and millionaires. And here all of us environmental people, we’re all struggling, poor. We’re trying to do the good work for the rest of humanity and we can’t. We can’t just do this alone, we need to find ways to fund ourselves and to make ourselves self-sufficient, so if those donations don’t come in that month I’m not going to starve to death.”

The Spirit of the Buffalo camp was a site intended for prayer, education and nonviolent direct action against the Line 3 pipeline. In May 2020, right before McManus spoke to Branch Out, the camp was burned down in an arson attack. Still, after the attack, her words continue to inspire hope, unity and action for preserving life:

“The unity that we need is not just because it’s time for hate to end. It’s because if we don’t come together and help each other, the people that are doing what they’re doing to this land are going to succeed. And we will be left with nothing, and we will all die, and that it is not going to be good. We will all suffer the consequences of what our actions are right now. And we can either decide to learn to get along and help one another, and pray and hope that whatever comes out of those prayers… Because we say in our culture when you go into sweats, you go in there to see something, to see a vision, to have a vision. Many people, I think, need to have more visions to see what it is that we can do to help one another because right now we are allowing the government to control everything that we do because everyone is locked down. So there’s more to come, my dear, a lot more.”